If you were to open any legal document related to the maritime industry, one term that would catch your attention is “lien”.

The dictionary definition of lien states, ‘The right to take another’s property if an obligation is not discharged.’

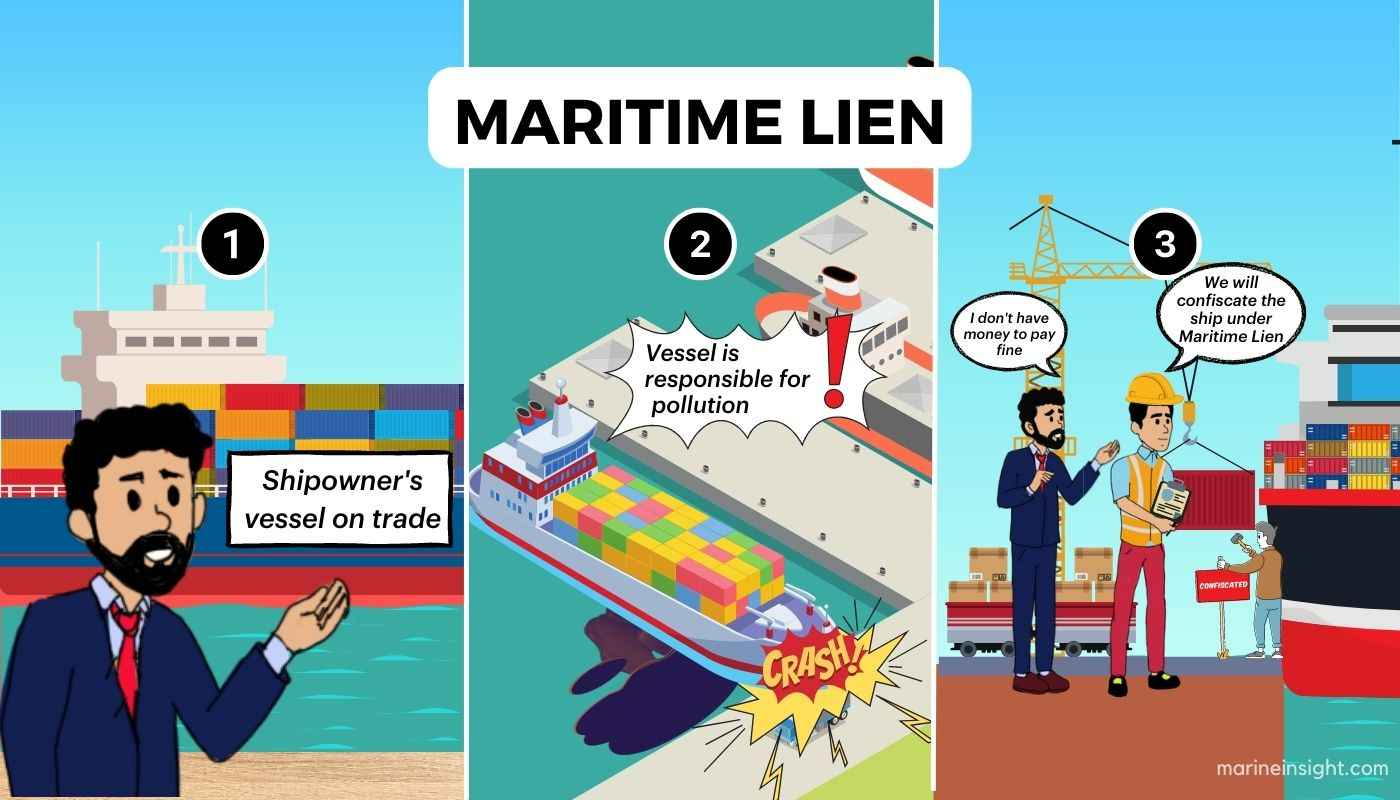

In simple terms, Lien means that if a person owes something to another person, the latter can take custody of the former’s property until the debt due to him is cleared. Even in maritime law, there exists a concept of a maritime lien.

This article will look at this important facet of the shipping industry and its role in maritime litigation. One of the biggest problems that plague shipping firms is an incomplete knowledge of Admiralty Law.

With this article, you will know about the pros, cons, and technical details that govern a maritime lien. With a wide array of information on the topic, this is your go-to article on everything to do with a maritime lien.

A maritime lien is a very important aspect of maritime law. A maritime lien can arise even when the ship owner does not directly contract the goods or services. Traditionally, such liens did not arise for goods or services provided in the home port as owners were local and would possibly know the supplier, who decided whether to furnish credit or not.

However, the Federal Maritime Lien Act, enacted in 1910, offers a maritime lien to the supplier of necessities irrespective of the location. The US is one of the few nations that accept a lien for “necessaries”.

The fundamental difference between a maritime lien and the normally applicable Lien is that in the case of the former, the liability of the contract falls on the ship and the other particulars (equipment and parts) of the ship rather than the ship’s owner, as it is the case of the latter where the person responsible is liable to pay the Lien. Briefly put, a maritime lien assumes that the guilty party in case of a maritime problem is the ship by itself rather than the shipowner.

Also, another difference between maritime liens and other liens is that the former can only be enforced under the jurisdiction of a federal court. Interestingly, unlike other countries, the United States is not a signatory to ship arrest conventions. A federal maritime lien need not be recorded anywhere, but one can register it with the US Coast Guard.

While this may seem to be a novel and confounding concept, it is integral to maritime regulations that enable investigators to establish a paper trail in case of litigation.

Maritime liens are unique as they view the vessel as a legal entity apart from its ownership. They are governed by commercial instruments, Maritime Laws and the Maritime Liens Act. Most liens arise from torts, contracts and services, including salvage and towage, preferred ship mortgages, seamen’s wages, claims of repairs, and civil wrongs such as personal injuries or collisions during vessel operations.

It was regarding a maritime lien that the Ship Mortgage Act was enforced in 1920. A preferred ship’s mortgage is a kind of maritime Lien on the mortgaged vessel, created with consensus from both parties and recorded at the National Vessel Documentation Center.

Although the ship is considered guilty in case of an accident, the vessel owner must represent the vessel in all legal proceedings. Thus, they must repatriate, re-compensate, or suitably comply with the regulations of the admiralty court “on behalf” of the vessel.

Such a legal clause that considers inanimate objects for Lien is known as a “proprietary instrument”.

It has two main components:

The reason for this seemingly convoluted system of maritime litigation is that a vessel is integral to the investigations conducted for an accident. The vessel may be sold and refurbished if charges are only brought against the owner. This change of ownership affects integral aspects of the investigation, which is the primary purpose behind a maritime lien being a proprietary instrument.

Another reason is that since the maritime industry imposes high fines that tend to be exorbitant, it can be challenging for the offending shipowner to pay dues.

A lien allows claimants to stake ownership of the vessel if the owner does not adequately compensate them. Such claimants are known as “lienholders”, and Res lien provides them with relief measures in case the owner files for bankruptcy or cannot fulfil litigation requirements.

A maritime lien is designed to prevent the shipowner from selling the vessel with a clear record while it is still under investigation. Thus, it is paramount that the Lien must be discharged or terminated for future sales with a clear record. An analogy of this Lien is as follows:

For a car involved in an accident, the car’s condition before the incident is important for investigators. Details of past services, accidents, and owners are also required to establish the role played by the driver (or car owner) in the incident.

If the vehicle is sold during the investigation, it may be difficult to trace and resume work. The new owner might have serviced it or moved to a different location.

Thus, a certificate must be issued before transferring ownership, stating that the vehicle is not involved in any ongoing investigations and has a clean record. Note that this certificate is for the vehicle and NOT for the car owner.

Similarly, for transferring ownership of a vessel, the Lien must first be terminated. This is commonly achieved by way of settling the claim.

The owner can pay the fines, waive his ownership of the vessel, sell or auction it to the authorities for realizing payments of the affected parties, or legal foreclosure of the vessel. If the owner intends to pay the fines rather than auction the vessel, they must inform the court of maritime law at the earliest.

Rem auctions are commonly applied in case of international accidents, where legal authorities sell the vessel to a bidder to clear the vessel of any involvement in the incident. This ensures that the vessel can begin a new lease without being party to the incident, while the authorities can receive payment to fund the compensation efforts.

In extreme cases, the destruction of the property under consideration (vessel or other equipment) can remove the shipowner’s liability and the subsequent Lien. This can only be achieved by the vessel’s destruction and not in part. Thus, attempting to salvage a section while continuing to operate the vessel is not grounds for terminating the Lien. In such cases, the lien transfers to the operational section.

Lastly, certain judicial rulings state that the Lien must be claimed within a set period. This indicates that the individual or organization claiming the Lien has exercised due diligence in good faith. This is used to prevent the claimant from going back on their word to claim and recover damages at the earliest. It is also known as “estoppel” in legal terms and is classified as a form of judicial sanction.

A few of the important features and characteristics of maritime Lien can be explained as follows:

The lateness in the enforcement of the maritime Lien by the lien holder to judge whether the Lien needs to be terminated or not is decided based on the causes and factors of the delay. There is a specified period provided by which the lienholder has to file the claim for the Lien.

A maritime lien is a complete series of legal measures to safeguard the rights of affected parties, requiring detailed features that encompass possible issues on the vessel. Some of these protected features under admiralty law are:

Rem and Personam are Latin terms used in law to indicate the party against whom the case is brought. Rem refers to property, while Personam is against an individual and is used to differentiate liability in judicial proceedings.

In Rem action, it is brought against the vessel, cargo, freight, or equipment attached to the ship (attached legally, not physically). The reason for a convoluted system of Admiralty Law for such claims is because of the ease with which a guilty party can be assigned.

For instance, the organizational leadership that manages a shipping company is not comprised of a single shipowner. Instead, there are multiple individuals led by a chairperson. Certain smaller vessels can have a single shipowner, in which case the same “in rem” proceedings apply.

Instead of a time-intensive investigation to identify the liable shipowner and the responsible parties, the liability is attached to the vessel. While owners and operators might change, the ship alone remains constant and can be identified easily for legal proceedings.

Another reason is the differing jurisdictions of the various parties involved. To prevent responsible parties from escaping the legal system by arguing that they are outside the jurisdiction of the admiralty court, the ship can always be held liable for the damage. It also overcomes the issue of different registration procedures across countries.

Lastly, by bringing an In Rem a maritime lien claim, the affected parties are assured of receiving payment either by security by the shipowner or by selling the res (the property).

In this article, a maritime lien’s terms and legal implications have been laid down. Another commonly used term that is often confused is the shipowner’s Lien.

In the case of a maritime lien, the affected parties can stake a claim on the ship, with a preference for the earliest claimants. In such cases, the proceeds from the vessel are used for adequate compensation. The shipowner assumes the responsibility for the ship and is liable to meet damages.

However, in some scenarios, the shipowner is also a claimant. For instance, if the shipper or maritime carrier defaults on payment for carriage of goods, the shipowner recovers costs from the Lien on cargo or containers on board. “Lien” arbitrarily refers to a stake, claim, or legal right to possess cargo. The cargo is maintained as a form of security against possible payment defaults by the shipper.

Fraudulent companies often front a shipper who is incapable of payment. Once the voyage is complete, they default on payment and claim bankruptcy. To prevent the loss incurred by the shipowner, the shipowner’s Lien empowers them to use cargo as security. This is the primary difference with a maritime lien.

In some countries, the shipowner’s Lien is not used, and only a maritime lien is applicable for claims by both affected parties and the owner.

A maritime lien is not without its controversies. One of the most popular ones is the concept of the ownership of the liability. Since a maritime lien invokes the liability on the ship and its equipment, it is sometimes said that this aspect of the marine law opposes ‘the entire world.’

The contractual parties to any agreement must follow the jurisdiction of a specific country determined based on mutual intergovernmental trade agreements. However, using a maritime lien brings the conflict of law to the fore. The various legal authorities that are eligible to make regulations or rulings on maritime law are:

However, controversies or no controversies, it cannot be denied that maritime Lien as maritime law is a highly influential force.

You might also like to read-